09

FATA MORGANA

Austria 2010-2012 / HD - DCP / black and white / 1:1,78 / 3.1 mono / running time: 140 min. (25f/s)

cast: Giuliana Pachner, Christian Schmidt, Awad Elkish

sound recording (Libya): Leo Schreiner / artistic collaboration: Maria Schreiner

music, sound recording and mixing: Johannes Schmelzer-Ziringer

concept, realisation, cinematography, editing: Peter Schreiner

supported by: the Austrian Federal Ministry for Education, Arts and Culture - Innovative Film Austria,

Vienna City Administration, cultural department

world distribution: echtzeitfilm / sixpackfilm

Int. Filmfestival Rotterdam 2013 / The Netherlands (International Premiere)

Diagonale 2013, Graz / Austria

Bradford International Filmfestival 2013 / Great Britain

New Horizons International Filmfestival 2013 / Poland

Bildrausch - Filmfest Basel 2013 / Switzerland

Transilvania International Filmfestival 2013, Cluj / Romania

48. Karlovy Vary International Filmfestival 2013 / Czech Republic

37th São Paulo International Filmfestival, 2013 / Brazil

42nd Festival du nouveau cinema 2013, Montreal / Canada

copenhagen architecture x film festival 2014, Copenhagen / Danmark

Cinemigrante International Filmfestival 2016, Buenos Aires / Argentina (as part of Focus Peter Schreiner)

Ein Mann, eine Frau,

beide

vom Leben gestreichelt wie gegerbt. Mal sind sie in einer Wüste, meist aber in einem verfallenen Haus in einer Landschaft, unwirklicher als die dunkle Seite des Mondes. Sie sprechen miteinander,

füreinander, aneinander vorbei, zueinander, umeinander. Sie sprechen von ersten und letzten Dingen, mäandernd, sich rückversichernd, forschend, fragend, in Bekenntnissen und Reminiszenzen,

einander umkreisend, und immer in Gedanken-, Satzfragmenten. Wonach suchen sie dabei? – Vielleicht: einem Wort, Gefühl, durch das man ruhiger dem Ewigkeitsschrecken begegnen kann. Das alles in

einem kristallinen Schwarz-Weiss, in Bildern wie Monolithen, voller Töne klar und hart.

Peter Schreiners Werke haben sich immer schon allen Definitionen verweigert – sie sind stets Hybride, Spiel-, Dokumentar-, Experimentalfilme in einem; genauer wäre es zu sagen: Sie sind unentfremdet, gestaltet exakt entsprechend seinen Bedürfnissen wie Wünschen. Für Schreiner ist das Kino ein Weg zum Menschen, ein Angebot zur Begegnung, damit auch eine Aufforderung zur Konfrontation mit sich selbst. FATA MORGANA ist mit das Schönste, wie Notwendigste, was das Kino der letzten Zeit hervorgebracht hat – ein Werk der Selbstentäusserung, -befragung, erfüllt von einer ganz raren, sinnlichen Spiritualität.

(Olaf Möller, 2013)

Was wird von dieser Wüste bleiben?

Ich hasse meine Ängste. Aber wohin soll ich fliehen?

Wo ist der Ort, an dem ich bleiben kann?

Denken, ohne zu fühlen? Fühlen, ohne zu denken?

Mein Leben ist ein Haus am Rand der Wüste. Drin bin ich geborgen und gefangen.

Und Du bist da. Nah und doch fern, vertraut und doch fremd.

Und das, und alles, ersehnen und fürchten wir. Wir können nicht anders.

Giuliana und Christian wohnen in diesem Haus, in mir, in meinem Leben.

Giuliana: „…ich stelle mir die Seele so vor: ein Haus mit verschlossenen Türen, die man sehr vorsichtig öffnen muss…“

Christian: „…da gibt es etwas, das wir ergründen sollen. Doch ich bezweifle, ob man zufriedener ist, wenn man es ergründet hat…“

Ihre Wunden sind meine Wunden. Gefühl und Gedanke zugleich.

Und es wird keine Liebesgeschichte. Oder doch?

Soll ich anfangen, meine Ängste zu lieben?

Giuliana: „…vielleicht hat dieser Tod draußen, der schon viele vertrieben hat, auch unsere Gefühle vertrieben?...“

What will be left of this desert?

I detest my fears. Where shall I seek refuge?

Thinking without feeling? Feeling without thinking?

My life is like a house on the fringe of the desert where I feel both secure and shut in.

And there is you. Close and yet beyond reach, intimate and yet unfamiliar.

And it is this we long for and are afraid of. We cannot do otherwise.

It is this house Giuliana and Christian live in, within me, in my life.

Giuliana: “… I imagine man’s soul to be somehow like that: full of doors closed …and you have to open them very

carefully…”

Christian: “…you think you are controlling all …but it is something else …and that’s what has to be found out …and the question

then is …having gotten on the bottom of it …will you then be happier? …that’s what I’m sceptical about…”

Their distress is my distress. This is both a feeling and a thought.

And no love story will come out of it. And yet it may.

Shall I start to love my fears?

Giuliana: “…maybe this death outside …having driven away already many people …has chased away our emotions as well?...”

(translation: Sabine Rachbauer)

kolossaler filmischer Rorschach-Test

Als letzter Teil einer inoffiziellen Trilogie ambitioniert herausfordernder Charakterstudien Schreiners, der selbst schneidet und dreht (auf kristallklarem

schwarzweiß-Digitalformat) wie auch für Regie und Produktion verantwortlich zeichnet, ist FATA MORGANA sogar noch schwieriger als BELLAVISTA (2006) und TOTO (2009), die bereits schon stilistisch

zu streng für die meisten Festivals waren. Aber nichtsdestoweniger hat sich Schreiner nun als bedeutender, bewundernswert kompromissloser und unentbehrlicher Künstler etabliert, als einer, der

das Kino als seine ganz persönliche, leise Art des Ausdrucks gefunden hat. Sein so intimes, aber episch-breites Statement zur condition humaine, gedreht in Deutschland und Libyen, mit zwei

philosophierenden 'Protagonisten', stellte dieses Jahr die anderen Weltpremieren in Rotterdam in den Schatten. Feinfühliger Umgang im Hinblick auf die Präsentation dieses Films wird erforderlich

sein: er mag gewaltig und imposant sein, aber es ist auch etwas gefährlich Zerbrechliches und Empfindliches an diesem Werk, das sich anfühlt wie ein ungefilterter Einblick in die gequälte Seele

seines Herstellers. Mit 140 Minuten Laufzeit macht FATA MORGANA, benannt nach einer Luftspiegelung, wie sie in Wüstenregionen vorkommt, nur wenige Zugeständnisse an konventionelle narrative

Formate oder Montage-Rhythmen, vielmehr steckt der Film ein Gebiet ab jenseits der traditionellen Unterscheidungen von Fiktion und Dokumentation. Wir beobachten Giuliana Pachner und Christian

Schmidt, ein Duo mittleren Alters, manchmal in unbequem nahen Close-ups, die jede Pore und jedes Haar sichtbar machen. Zwei Drehorte werden verwendet: die Libysche Sahara, in der Nähe einiger

nicht identifizierbarer Industriegebiete, und - wie es scheint, verlassene - Gebäude im Landstrich der Lausitz in Deutschland. Das Paar redet, oder wird still. Small Talk ist verboten: Der Satz

"wie schwer ist Leichtigkeit?" ist ein gutes Beispiel dafür, wie 'direkt' dieser Austausch stattfindet. Pachner und Schmidt werden einzeln und zusammen gezeigt - in der Wüste gesellt sich - sehr

selten - eine Art Reiseführer zu ihnen, Awad Elkish. Aber dies ist kein 'Reisebericht': Stillstand ist das Gebot der Stunde, eher als Bewegung, eine Samuel Beckett - Schwingung, die vermuten

lässt, dass in der Vergangenheit etwas Schreckliches oder Wunderbares passiert ist und dass es in Zukunft wieder geschehen wird. Das Jetzt aber ist von Passivität und Nachsinnen bestimmt. "Wir

nehmen verschiedene Realitäten wahr", wie Giuliana - Hauptdarstellerin aus BELLAVISTA - bemerkt. FATA MORGANA ist in seiner Gesamtheit am besten als eine Art kolossaler filmischer Rorschach-Test

zu schätzen, einer, der von allen jenen, die 'dran bleiben' und diese Reise hinein in bedrohliche innere Bereiche mitvollziehen, ganz unterschiedlich aufgefasst wird. Viele werden sicherlich

lange vor dem Ende des Films die Flucht ergreifen, 'erfroren' durch den atmosphärischen Bogen tiefer teutonischer Schwermut, die über diesen langen, ereignislosen Sequenzen hängt. Von Zeit zu

Zeit jedoch bietet Schreiner ein Bild von atemberaubendem Glanz, findet einzigartige Konfigurationen von Sand und Himmel, zaubert unverwechselbare Stimmungen mit seinem Soundtrack, und beweist

damit: wir befinden uns in den Händen eines echten Meisters. FATA MORGANA ist eine Sache des Vertrauens - das, was undurchdringlich langsam und mühsam zu sein scheint, erweist sich - in der Tat -

letztendlich als lohnend. Ein erfrischendes Gegenmittel zu fast jedem aktuellen Trend im zeitgenössischen Kino, mit Bildern, die so viel zu tun haben mit Malerei und Fotografie wie mit Kino, und

einen seltsam hypnotischen Bann ausüben, der noch lange anhält nach der phänomenalen Schlusseinstellung. Eine großartige Verdichtung menschlicher Vergänglichkeit ist an uns vorübergezogen.

(Neil Young, Hollywoodreporter, 2013)

colossal cinematic Rorschach test

Last in an unofficial trilogy of ambitiously challenging character-studies from Schreiner, who edits and shoots (on crystalline black-and-white digital video) as well as producing and directing, it's even more difficult than 2006's BELLAVISTA and 2009's TOTO, which proved too austere for most festivals. But Schreiner is nevertheless now established as a significant, admirably uncompromising and necessary artist who happens to have chosen cinema as his mode of quiet expression. His intimate but epic statement on the human condition, shot in Germany and Libya and featuring two philosophically-minded "protagonists," dwarfed the other world premieres at Rotterdam this year. Delicate handling will be required in terms of the film's presentation: vast and stately it may be, but there's something perilously fragile and sensitive about a project that feels like a raw glimpse into its maker's tormented soul.

Running at 140 minutes, FATA MORGANA, named after a mirage common to desert regions, makes few concessions to conventional narrative formats or editing rhythms, staking out a territory beyond traditional distinctions of fiction and documentary.

We observe, sometimes in uncomfortably close close-up that reveals every pore and hair, middle-aged duo Giuliana Pachner and Christian Schmidt. Two locations are used: the Libyan Sahara, close to some unidentifiable industrial zone, and what look like abandoned buildings near countryside in Lausitz, Germany. The pair talk, or fall silent. Casual chat is verboten: "How heavy is lightness?" is about as straightforward as these exchanges get.

Pachner and Schmidt are shown apart and together - in the desert, they are very occasionally joined by a guide, Awad Elkish. But this is no "travelogue:" stasis is the order of the day rather than movement, a Samuel Beckett vibe that suggests something dreadful or wonderful may have happened in the past and that something may happen again, but that the now is defined by inactivity and rumination. "We perceive different realities," as Giuliana - chief focus of BELLAVISTA - notes. And FATA MORGANA is best appreciated in its totality as a kind of colossal cinematic Rorschach test, one which will be understood differently by all those who embark upon and stay with this journey into forbiddingly complex interior terrain.

Many will undoubtedly escape long before the conclusion, frozen out by the arch atmosphere of deeply Teutonic gloom that hangs over these long, uneventful sequences. But from time to time, Schreiner delivers an image of such breathtaking splendor, finds some unique configuration of sand and sky, conjures some unique mood with his soundtrack, that he proves we're in the hands of a genuine master.

FATA MORGANA is a matter of trust - that which appears to be impenetrably slow and tedious, will, in fact, ultimately prove worthwhile. A bracing antidote to just about every trend in contemporary cinema, the picture has about as much in common with painting and photography as cinema, and exerts a weirdly hypnotic spell that haunts long after the stunning final image - a superb encapsulation of human transience - has passed.

(Neil Young, Hollywoodreporter, 2013)

als würde sich das Innerste in die Außenwelt projizieren

Noch ein Österreicher sorgte in Rotterdam für Aufsehen: Peter Schreiners monumentale existenzielle Studie „Fata Morgana“ feierte dort Weltpremiere. Schreiner, eine Zentralfigur des heimischen Sensibilismus, folgt darin einem gealterteten Paar – Giuliana (die Zentralfigur von Schreiners preisgekröntem Film „Bellavista“) und Christian Schmidt (einst Titelheld von Niki Lists „Müllers Büro“). In ruhigen Gesprächen stellen sie sich, jedes Wort abwägend, ihren Ängsten – während sich Schreiners Kamera spürbar jedes Bild genauso hart erkämpft:

In ungewöhnlichen Kadragen studiert er die Gesichter und Körperteile und liefert atemberaubende Landschaftspanoramen von der Lausitz und von Libyen – als würde sich das Innerste in die Außenwelt projizieren, wie einst in Ingmar Bergmans „Persona“. In der privaten Suche spiegelt sich die gegenwärtige Krisenzeit: Weltkino im besten Sinn.

(Christoph Huber, die Presse, 2013)

merciless yet tender

Austrian experimental documentary maker Peter Schreiner undertakes a psychoanalytic quest for human existence. It’s a cross between Freud and Sartre, magical and minimalist, as long as you dare. Two wrinkled lovers, marked by life, expose their deepest inner emotions. Giuliana compares the vaults of her spirit with closed doors that you ‘have to open cautiously'. 'But,' Christian wonders, 'does that make you happier?' They talk slowly and calmly, looking for the right words for their inner demons. It all comes down to reason and feeling and where the two meet. About reality that looks both familiar and alienating. And about the impossibility of understanding yourself - let alone anyone else. Schreiner’s magnum opus is spiritualising but also stimulating. Majestic panoramic landscape shots fade into close-ups of faces, meticulously examined by the camera. As such, Schreiner is hard yet humane, merciless yet tender.

(Chinlin Hsieh, IFFR, 2013)

"Der Raum ist ausgeräumt."

Wollte man den Umfang des Vorhabens von Peter Schreiners FATA MORGANA in einem Satz ermessen, käme der Titel des ersten Teils von Martin Heideggers "Sein und Zeit" gerade recht: "Die Interpretation des Daseins auf die Zeitlichkeit und die Explikation der Zeit als des transzendentalen Horizontes der Frage nach dem Sein." Mit nicht weniger als der Frage nach dem Sinn von Sein nämlich, d.h. mit einer Frage, für die der aufgeklärten, säkularen Moderne das Verständnis fehlt, sind die drei Protagonisten des Films (Awad Elkish, Christian Schmidt, Giuliana Pachner) 140 Minuten lang beschäftigt.

Allerdings nicht im Sinn einer ontologischen Existenzialanalyse, sondern einer Versuchsanordnung, deren Parameter Schreiner gleich in der ersten Einstellung offenlegt. Sie zeigt die Protagonisten als drei Figuren in einer Landschaft. Awad Elkish ergreift das Wort: "Der Mensch musste einen Bezugspunkt oder einen Halt finden, und das ist schon ein kreativer Prozess." Der Satz ist weder an seine Mitspieler gerichtet noch an ihn selbst, er geht an der Kamera vorbei in ein unbestimmtes Nirgendwo dahinter, adressiert eine Stelle, an der der Regisseur sich befinden könnte, die Crew oder einfach die Fortsetzung der sichtbaren Landschaft – jene Wüste, deren Funktion für die Versuchsanordnung Awads nächste Äußerung klarstellt: "Der Raum ist ausgeräumt."

Tatsächlich könnten die ausgeräumten, verlassenen, leeren Räume geologischer und industrieller Wüsten in Fata Morgana als Sinnbild der Sinnsuche gelesen werden: In Heideggers Verständnis würden sie die zumindest räumliche Abkehr von jener uneigentlichen "Flucht des Daseins vor sich selbst" bezeichnen, das im Besorgen der Alltagsgeschäfte aufgeht. Der Lesart widerspricht, dass Kamera und Mikrofon unablässig die konkrete materielle Präsenz der leeren Räume betonen: Mag die Zeit der transzendentale Horizont sein für die Frage nach dem Sein, im Kino des Peter Schreiner kann diese nur gestellt werden im Hier und Jetzt des gelebten Augenblicks.

(Vrääth Öhner)

“The space is cleared out.”

Should one attempt to judge what Peter Schreiner’s FATA MORGANA intends to do in a single sentence, then the title of the first division of Martin Heidegger’s Time and Being would be rather fitting: “The Interpretation of Da-sein in terms of Temporality and the Explication of time as the Transcendental Horizon of the Question of Being.” The film’s three protagonists are occupied 140-minutes long with no less than the question of the meaning of existence. In other words, they are busy with a question for which the enlightened, secular Modern era has no understanding.

However, not in the sense of an ontological existential analysis, but rather, an experiment whose parameters Schreiner reveals right away in the first take. It shows the protagonists as three figures in a landscape. Awad Elkish rises to speak: “People had to find a point of reference or a foothold, and that, already, is a creative process.” The sentence is not directed at the other actors, or at himself; it passes by the camera, to an undefined nowhere, addresses a place where the director could be located, the crew, or simply the continuation of the visible landscape - the desert, whose function in the experiment is clarified by Awad’s next statement: “The space is cleared out.” In fact, the cleared-out, deserted, empty spaces of the geological and industrial deserts in FATA MORGANA could be interpreted as symbols of the search for meaning. In the sense of Heidegger, they would at least identify a spatial turning away from that improper “Dasein’s flight before itself,” which arises in taking care of everyday business. The interpretation is contradicted by the fact that the camera and microphone persistently emphasize the concrete, material presence of the empty spaces: Perhaps time is the transcendental horizon for the question of being, but in Peter Schreiner’s film, it can only be posed in the here and now of the lived moment.

(Vrääth Öhner, translation: sixpackfilm)

voidlike negative space

Austrian filmmaker Peter Schreiner's FATA MORGANA, suffuse in its every digital pixel with impassioned anguish, abstracts a relationship between

two actors into an experience, resolutely painful and searching, of two souls. Two humans fill the frames, both seemingly of the same craggy later middle age, but the woman aged physically beyond

her years, and her ticks, her halting words, and most especially her eyes tell expansive but enshrouded stories of a personal history of endless crestfalls and hurt. Realism here is only digital:

faces as big as landscapes, details of beard bristle and eye wrinkle beyond comparison, and landscapes themselves—German interiors, Libyan exteriors—voidlike negative space.

There is no realism in the dramaturgy, no plot, no everydayness. A rare scene of the man eating food seems a shock in a film where people don't

eat, sleep, work, do—they exist, search within, ricochet glances out to search the other before turning, again, inside themselve, asking silent questions, voicing rare, fragmented thoughts. It is

the strongest cinematic expression of ghost and ghostly existence I have seen. All is held, all is almost. Sentences are not completed; exchanges search for words, always abstract, to describe a

real life experience and feeling that could not possibly have happened here, in the digital sheen, like an unfurling silver nitrate photography, of Schreiner's filmworld. This world is elsewhere,

as are its two inhabitants. Most powerful of all is that these sole survivors (only one other person is visible in the film, an unexplained presence in the Libyan desert) bespeak of an intimacy

between the two that is deep and profound and loving—but a mystery. It is one which invokes a foreboding sense of documentary, especially because the man has a caretaker aspect to him, a

difference and a kindness, in his way of of looking after the woman that is not returned in measure, and that which ties the film back to Loznitsa's Letter and infirmity...and exile. The level of

dramatic abstraction feeds into this as well, evoking a piercingly vague non-concreteness to dialog, exchanges, moments, evoking dementia, trauma, amnesia. Yet this

psychic-emotional-mindful/lessness shares equal time and space with the textures of faces and hands, the sharpness or whispiness of irises, the satin digital pattern of a house or a landscape. It

evoked for me two distinct and different digital portraits of age, distance, and loneliness from 2012, Stephen Dwoskin's final film, Age Is... and Jean-Claude Rousseau's Saudade, taken into outer

space—or perhaps no space, taken into a very psychic and intimately physical netherworld.

(Daniel Kasman, mubi, 2013)

die Suche nach dem Ich

(...) wie du uns eintauchst in eine ganz eigene traumhafte Welt, in der wir uns und unsere Gefühle anschauen müssen, in der wir in den Gesichtern von fremden Menschen unsere Ängste, Zweifel und Hoffnungen sehen können - das gibt mir, inmitten aller Vergänglichkeit und Angst, Zuversicht.

Nicht nur, was und wie du es zeigst, sondern schon allein dass du es zeigst, dass dieses angstvolle Fremdsein Thema ist, das Verstanden-sein-wollen, das Gesehen-werden-wollen, als ganzer Mensch - mit allen schwarzen, tiefen und furchteinflößenden Seiten der eigenen Existenz, die Suche nach dem ich im Spiegel und im Gegenüber, die so schwer und manchmal unmöglich scheint -

(Judith Zdesar)

Was zu hören und zu sehen ist. Es. Nichts anderes.

Gerade dadurch, dass der Film rigoros auf jede Art von Erklärungen verzichtet, dass er also nichts beschreibt, sondern selbst Schrift, Sprache und Ausdruck ist, überträgt und überlässt er mir die Last und das Vergnügen, selbst der Rätsel Lösung zu finden. Zu finden! Denn jeden Versuch, nach einem Sinn dieses Films zu fragen, hebelt der Film selbst aus, weil die Art und Weise seiner Konstruktion ein Sich-zurücklehnen und ein Von-außen-hinterfragen konterkariert. Dieser Film verweigert, zu erklären. Bewusst. Und er kann es sich leisten, weil er - in Hinsicht seiner kinematographischen Elemente - untadelig und einfach perfekt ist.

(...) Insofern stellt er für mich als Zuschauer eine doppelte Herausforderung dar, in dem er mich einerseits durch seine Materialität "gefangen nimmt und verzaubert". Andererseits wirft er mich ganz auf mich selbst zurück. Existentiell. Ich finde Antworten, Sinn darin und dann, wenn ich mich dem Film er-öffne. Mit allen Wagnissen und Unvereinbarkeiten, gegen alle Regeln von Logik und Vernunft.

Dieser Film IST das, was ich als Zuschauer in mir ent-decke.

Hier ist alles offen gelegt, hier gibt es kein Spiel mit gezinkten Karten, hier ist zuallererst das, was zu hören und zu sehen ist. Es. Nichts anderes. Töne und Bilder meinen nicht, sie sind.

(Michael Pilz)

this search for your own self

(…) The way you lead us into a strangely dreamlike world in its own way, in which we have to have a look at ourselves and our feelings, in which we can discover our fears, doubts and hopes in other people’s faces, gives me a feeling of confidence, despite all transitoriness and anxiety.

Not only what and in which way you show it, it’s just the very fact that you show it, this state of being unknown to others, full of anxiety, the longing for being understood, the longing for being seen, as a whole – together with all the dark, deep and terrifying aspects of man’s existence, this search for your own self in a mirror and in others, seemingly so very difficult and sometimes impossible –

(Judith Zdesar, translation: Sabine Rachbauer)

Anything that can be heard and can be seen. Nothing else.

By being adamant in its refusal to give any explanation and by being script, language and expression itself, the film passes on and leaves the burden and the pleasure up to me to find a solution for the riddle. Any attempt to inquire as to the meaning of the film is thwarted by the film itself, for it is constructed in a manner that does not allow any consideration and any analysis from the outside. This film deliberately refuses to give any explanation. And it gets away with it, because – with regard to its cinematographic elements – it is beyond reproach and simply perfect.

(…) For the audience, the film is a double challenge. It is captivating and enchanting due to its materiality and it throws me back to my own self. In an existential way. Answers and a meaning thereof are found when I open myself to the film, accepting all the risks and inconsistencies, despite all reasoning.

This film reveals anything I may discover within me.

There’s no cheating. Anything that can be heard and can be seen is all that matters. Nothing else. Sounds and images do not give a meaning, they are.

(Michael Pilz, translation: Sabine Rachbauer)

Absolute zero point.

Two spaces, mainly. First, a house, arranged in two ‘wings' or rows – is it some now unused hotel? – with green trees (seen through black-and-white) visible out a window. Some shots of a river, possibly in the same general area. Second, a desert – sand, a distant horizon, rocks, stretching on forever.

If you stay to the end credits, to the 140th minute of Peter Schreiner's FATA MORGANA – and many viewers will not – you will learn that there are two shooting locations: Lausitz in Germany in the Sahara in Libya. Which explains something about the making of the work, but nothing about the work itself.

As you watch it, the film is a puzzle – but not one that is wanting you to provide a solution. Whenever any movie goes back and forth between locations as starkly different as these, the viewer's brain tends to a) pull them all together (no matter the logical or logistical difficulty) into one imaginary space or place; or b) try to construe a narrative trajectory: that there are various people in separate geographic spots, but somehow they are all going to meet up, and the dots between the places can then be joined up into lines.

I managed to perform both these mental operations, casually and pretty unconsciously, as I watched FATA MORGANA. I started seeing – hallucinating – the single, continuous space of a ‘house by the desert' (in homage to Fritz Lang's House by the River, 1950), especially as the two people we see in and around the house (more about them in a moment) are also seen walking, sleeping and talking in the desert sands. And there is something cinema-based, as well as reality-based, in this propensity: namely, that a fata morgana is itself an elaborate desert apparition, what is nicely called a superior mirage that forms on the hot, empty horizon. An imitation of life.

I also was ‘thrown' – or led – by the opening scene: three people in a desert, one of them (is it, in fact, director Schreiner? Another source tells me it's Awad Elkish) pontificating, mock-pretentiously, on the need to "find a point of reference... an inner stability." Because I could not yet identify any of these figures as full-blown ‘characters' in the film to follow, I took this trio to be some autonomous grouping, out in a desert... and on their way to an encounter (momentous or deflating) with the couple in the house.

Knowing from the first frame that it was a minimalist movie in the lineage of Albert Serra, I predicted – projected – that it would not be until the 70-minute mark that such an encounter actually began to manifest itself: mid-way breaks like this are as popular in art films as in Hollywood blockbusters these days. And at the 70-minute mark, there did seem to be some stirrings of change in the generally monotonous, non-action-based unfolding: a third person, more emphasis on the desert. But here my cognitive apparatus proved to have completely betrayed me. No plot is forthcoming in FATA MORGANA.

Schreiner's crypto-poetic statement on the sixpack website includes the line: ‘My life is like a house on the fringe of the desert where I feel

both secure and shut in'.

So this house-by-the-desert business is his personal fata morgana, too. It is also, evidently, some kind of mental projection - some kind

of interiority made exterior. As it seems to be for the two central ‘players' of the work, Giuliana Pachner and Christian Schmidt. (A little rummaging in the sixpack site also revealed that a

2006 Schreiner 35mm film, Bellavista, was a previous, 2-hour exploration of Pachner in what might be this same, odd hotel with two wings in Lausitz.) They speak of the desert a lot. Or rather,

they speak of silence, stasis, a draining away, the end of all thinking... which, in this context, amounts to the same thing as the desert, the image/symbol/figure/metaphor of the

desert.

I thought of the sand dunes (overdubbed with jazz music) that form mysterious interludes or punctuations in Pasolini's Teorema (1968). Eventually, one of PPP's characters will indeed have his naked, insane, screaming rendez-vous with this elemental desert. But is it really a narrative destination? Is this desert all around, or is it in his head? (Happy 66th Birthday, David Bowie.) It's not really a place he could have just driven to. It's always been within him, within us, within the film. And within the medium, too: cinema loves these deserts in which it disappears, is dissolved, expelled. As a filmmaker (David Lean or Lisandro Alonso, it doesn't matter), you want these images, but these images don't want you: the desert abhors mise-en-scène and fiction alike. And this dusty wave of non-love coming off the desert plain is really quite an attraction. A masochistic attraction. Marlene knew it when she kicked off her high heels and strode out across the sands for Gary Cooper in Morocco (1930), and Sternberg knew it when he ended that film on the dispersing void of particles and the whistling wind (especially poignant in crumbling old 16mm prints)...

FATA MORGANA: two people, a man and woman. I thought of the eternally-against-it, equally unglamorous couple of Hail (2011), and of Alain Badiou's recent declaration that, since absolutely everybody yearns for it and experiences it, love is among the only, the very few, universals. On the other hand: Schreiner's notes assure us that ‘no love story will come out of it. And yet it may'. But when? Like in the snowbound retreat of Philippe Grandrieux's Un lac (2008), we would be silly to ask questions about how these flesh-and-blood, ageing phantoms manage to eat, pay bills, or take a shower. The things that Pachner and Schmidt say to one another (or sometimes just to themselves) in this film, if you pluck them out and string them together, could have been uttered 50 years ago, as the robotic stutterings of an involuntary Surrealist poetry, by Lemmy Caution and Natasha Von Braun: The turning into stones of our emotions ... Forgotten and abandoned at the same time ... We find ourselves in a vacuum of time ... You must have the courage to stand this stillness ... I'm fascinated and completely worn out ... When I open the lid, pain and death escape from it ... Death and blood and a shot ... Anything but our thoughts ... To quit thinking ... Every day we are doubtful about ourselves ... Writing one's name on a wall to leave a trace of one's existence ... and pass on a despair ... How heavy is lightness? What does up and down actually mean? That is just a small selection.

But this is not Alphaville (1965) the film, or even Alphaville the place. Even sympathetic spectators will experience these solemnly uttered statements as lethal boomerangs back onto FATA MORGANA itself; and very likely Schreiner himself (as that strange prologue indicated) welcomes, and indeed programmed, this kind of reflexive irony. A typical artworld endgame manoeuvre, although the director's notes suggest that he has loftier things on his mind. The transmission of such things, in the public forum of cinema (and especially during a film festival) is always fragile.

It's a murky film, as feature-length avant-garde experiments, high on texture and low on plot, can sometimes be. It doesn't have the crystalline clarity of a Chantal Akerman non-fiction such as D'est (1993); but, then again, few films (of any sort) have that. There is a scene of sudden rain, crisp and real. There is a camera: it pans super-slowly, left or right, and on its brutal path creates a hundred different, sometimes arresting deframings (at moments reminiscent of Stephen Dwoskin's great testament Age Is...): stray ears, hair clumps, shoulders become as prominent and important as eyes and mouths and faces. The human is always decentred; yet, because it has leaked out into the imaginary desert of cinema, the human is everywhere, uncomfortably, stuck like grout between the frames, decaying and stinking before our eyes. There are landscape shots that achieve such stillness that you take them, for a while, as freeze-frames, but they are not: Schreiner has really found these places where nothing, nothing at all, moves. Not even the wind in the sands, not even the grain of the image. Absolute zero point.

(Adrian Martin, de Filmkrant, 2013)

taciturn

In his taciturn FATA MORGANA, Schreiner’s protagonists are exposed to desert formations as well as traditional European cultural landscapes and confronted with subtle soundscapes. On the wide screen, bodies, objects, materials and lighting combine to take high-definition film to its limits.

(Christa Blümlinger, IF-Katalog 2013)

the borders of the soul

FATA MORGANA!! A meditative, lengthy conversation about the borders of the soul, aging of the body, death, and love. Wonderful!

(Asli Ozgen-Tuncer, 2013)

a momentary occurrence in an ever-transient world

It’s difficult to know how Peter Schreiner formats his scripts, but in the English subtitles that accompany his latest film, each line of dialogue begins and ends in ellipses, which might be taken to suggest that the film and every incident within it is an interruption of some kind, a momentary occurrence in an ever-transient world. With its unhurried 140 minutes shared between a house in Lausitz, Germany and the remote terrain of the Libyan Desert, Fata Morgana is a gruelling but beautiful tester full of competing textures – in both the visual and material sense of the word – as a man (Christian Schmidt) and a woman (Guiliana Pachner) converse with one another on the meaning(s) of life, death, the world and how the three might interrelate.

This invigorating tone poem is far more difficult to describe than it is to sit through. Its title evokes Herzog’s meandering 1969 film of the same name, but better reference points might be Tarkovsky at his most arduously spiritual or the equally difficult and provocative black-and-white films of Elias E. Merhige. All of which is to say: not much happens, and yet the whole thing flies by. The film has a persistent emphasis upon the experiential: it wants to us to wander alongside its own ponderous musings, to participate in its thematic discussions, and to spend time figuring it all out. Whether or not one is convinced that the film is as interpretable as it presumably wishes to be is another matter, but Schreiner’s monochrome HD imagery binds spells in itself.

It’s not just in its glacial pacing that we see Fata Morgana is concerned with time; there are multiple temporalities at work in the film’s own language. Here, man and indeed woman are viewed as fragile and innately insignificant beings through planetary, geological and even perhaps cosmic frameworks. Here, humans are lonely figures trekking through space, constructing their own worldly perspective in order to combat feelings of temporal and therefore spatial isolation – just as they fashion their means of production from material resources in order to survive from one day to the next. Schmidt’s character looks to hold a tree branch like a gun, but then starts playing it like a guitar, chiming with that ape in the opening sequence of 2001: A Space Odyssey, which employs a bone as a weapon; the ability to reconfigure nature is the defining feature of homo sapiens.

Elsewhere, the sun gradually sets behind a dune; the moon floats high in the heavens. The unperceived and unperceivable violence of natural phenomena: facial wrinkles, the contours of time; a chunk of tree trunk, the fine details of human hair. And a contrast that recalls the repeated spatial juxtapositions of Roeg’s Walkabout (1970): one moment a house of bricks, another moment the vast expanse of a desert. Are reminders of our cosmic insignificance welcome or unhelpful, though? Schreiner presumably wants to elicit a range of views, but when Schmidt remarks that “there are people who fear death their whole life and forget how to live” and that “the anxiety can strangle you”, one might legitimately respond: speak for yourself.

(Michael Pattison, www.eyeforfilm.co.uk, 2013)

a visual poem

Probably the most challenging and unique film I've seen at this year's BIFF, FATA MORGANA is the newest work from director Peter

Schreiner and not so much a film as a visual poem.

There's no story to speak of. The film focuses on a man and a woman, but they say and do little, and there's no traditional "A

leads to B leads to C" continuity between scenes. Instead the film uses images of a barren landscape to conjure an intense feeling of emptiness and stillness, mirroring the characters' state of

mind as they muse on their own feelings of melancholy and the small comfort they find with one another.

FATA MORGANA is undoubtedly very beautiful, full of striking black and white images of a vast, empty desert and a cold, sterile

house. The slow pace and careful use of sound (and often lack of sound) do a good job of getting you in the right frame of mind and if you can accept the film on its own terms it's surprisingly

watchable.

Trying to decipher any meaning or intent from FATA MORGANA feels like a fruitless endeavour. It's essentially two hours and twenty

minutes of emptiness, and the small amount of dialogue never gives us more than a tiny glimpse into these characters' minds. People who are used to avant-garde filmmaking will probably find it to

be an excellent example of what can be done with this medium when conventional ideas of plot and character are disregarded.

Dave Rogers, yorkshiretimes.co.uk, 2013)

thanks to:

Awad Elkish

Bernhard Sallmann

Christina Schmidt

Diana Pachner

Edeltraud Noack

Elkish – family / Tripolis

Emmanuele Pachner

Hermann Krejcar

Ingomar Mangl

Jörg Noack

Judith Zdesar

Kathi Miedtank

Manfred Noack

Michael Pilz

Moawia Elkish

Olaf Hanspach

Rainer Komers

drivers / attendance / Libya:

Omar Greesch

Ibrahim Abosalah

Jalal Dubo

Ahmed Dalah

Ahmed Elhadad

cook / Libya:

“Dammah”

travel - organisation / Libya:

Ali Saidi - Safari Tourism Services

image processing / sound mix / subtitles / equipment:

echt.zeit.film

re-recording:

Listo-Videofilm GmbH

translations:

Sabine Rachbauer

subtitling / photos:

Paul Schreiner

assistance production / documentation:

Isabella Schreiner

consulting / organisation / tour guide / Libya:

Awad Elkish

consulting / locations / Germany:

Stephan Kaasche

production management:

Peter Schreiner

sound recording / Libya:

Leo Schreiner

music / sound recording / sound mixing:

Johannes Schmelzer-Ziringer

artistic collaboration:

Giuliana Pachner

artistic collaboration / assistance realisation:

Maria Schreiner

concept / realisation / camera / editing:

Peter Schreiner

production:

echt.zeit.film - Peter Schreiner Filmproduktion

supported by:

the Austrian Federal Ministry for Education, Arts and Culture

- Innovative Film Austria

Vienna City Administration, cultural department

filmed 2010 / 2011

Sahara / Libya

Lausitz / Germany

echt.zeit.film

2010/12

shooting format:

XDCAM-EX 1920x1080 25p, bw

audio: mono, 3.1

available prints:

1. Digital Cinema Package SMPTE/DCI - JPEG2000

Flat 1998x1080 / 25p / Audio: Digital 3.1 (mono)

english subtitled

2. HDCAM 1920x1080 / 25p / Audio: 2-channel-mono

english subtitled

3. BLURAY-DISC-DL 1920x1080

/ 25p / Audio: 2-channel-mono

4. QUICKTIME-FILE Apple PRORES 422 HQ 1920x1080

Audio: 3.1 (mono) or 2-channels (mono)

english subtitled or without subtitles

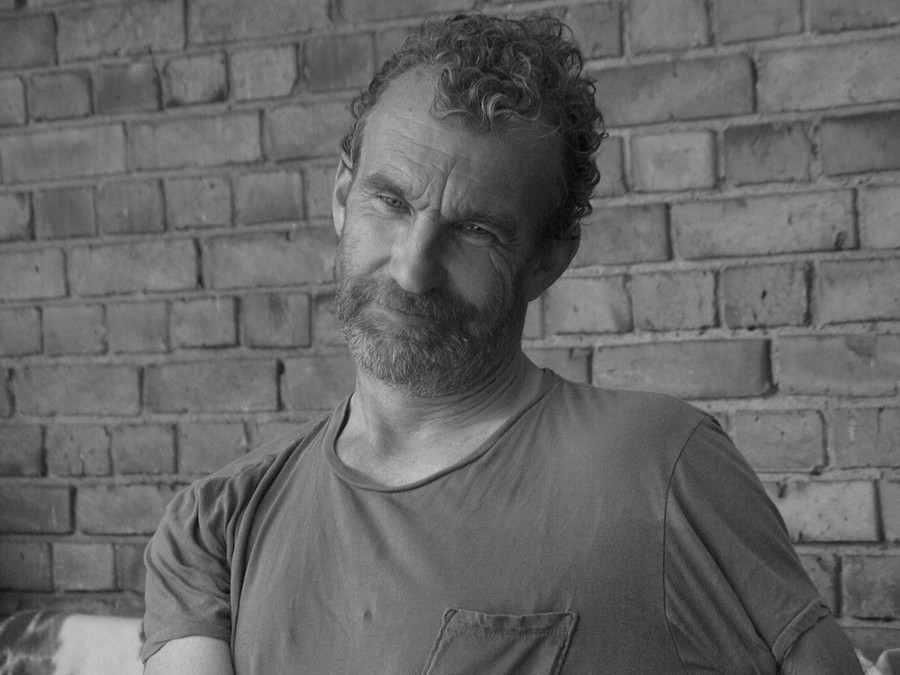

Arbeitsfotos

work photos

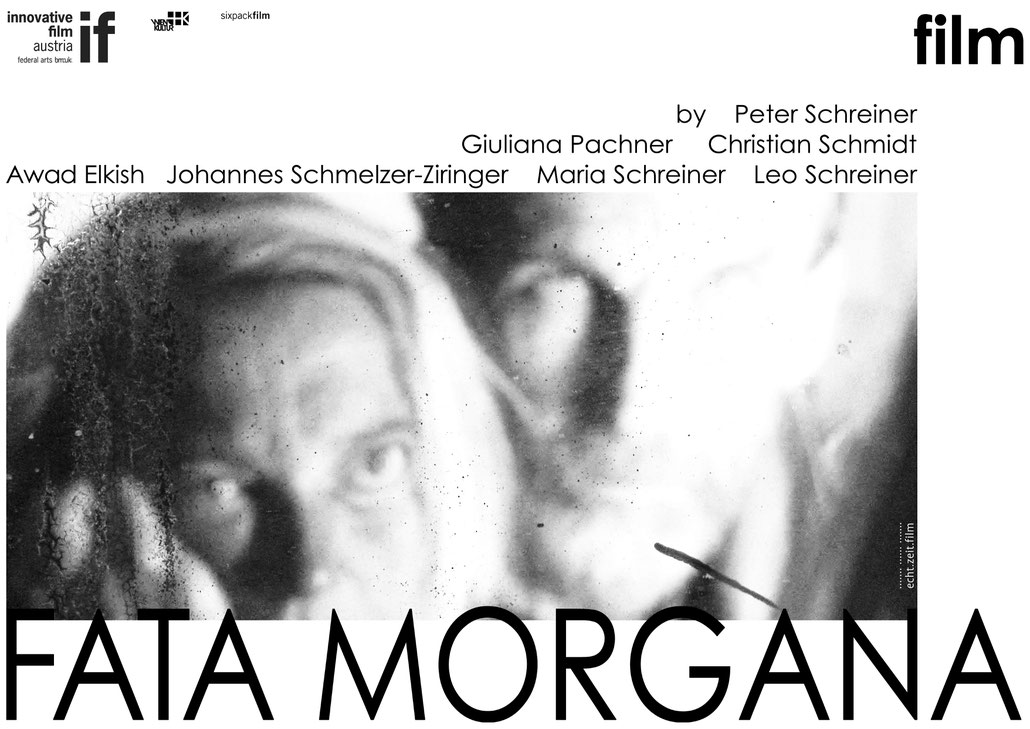

Plakat

poster

all texts, videos, pictures, document presentations etc. may be used, as long as the origin is marked by a link to www.echtzeitfilm.at

and no commercial aim is pursued.